Turing Completeness and Sid Meier's Civilization

Or how Civ is mathematically one of the hardest games in existence.

This is a less rigorous version of my paper Turing Completeness and Sid Meier’s Civilization, published in IEEE’s Transactions on Games. It’s shorter and better written than the original post, which is absolutely unreadable, from my website.

In this post I’ll talk about how some Civ games are Turing complete and undecidable.

Before you ask: yes, this means you could build things with Civ. Yes, it’ll take a while. Yes, it is impractical. Although, as someone said on reddit:

This is a mathematician’s work. We don’t do things because we can build things—we do things because we get to know things.1

Here what we learn is a statement on the expressive power of Civ’s rules.

In other words, I prove that some installments of Sid Meier’s Civilization are, in their generalised form, among the hardest games in existence.

The way the proof works, very loosely speaking, is by showing that one can build an actual, general-purpose computer inside a running game session of Civ (i.e., it is Turing complete). As a corollary, it means that in an infinite game of Civ you cannot figure out a set of moves that makes you win every time (i.e., it is undecidable).

To illustrate this I implemented a famous algorithm (the Busy Beaver) running in a game of Civilization: Beyond Earth!

Note: this is a fairly long post, so here’s the general structure:

Background: why why

Turing completeness: why are the rules so powerful

Undecidability: why is the game so hard

Implications: real-world Civ (including its AI), and how games can be theoretical models of computation (e.g., compared to parallel universe-based computation)

Conclusion: we conclude

The Gist of it

We’ll see how Sid Meier’s Civilization: Beyond Earth (Civ:BE), Sid Meier’s Civilization V (Civ:V), and Sid Meier’s Civilization VI (Civ:VI) are Turing-complete, and also are undecidable.

‘Turing-complete’ means that their ruleset is so powerful, that you could write and run arbitrary algorithms (programs) in running sessions of these games.

‘Undecidable’ means that there is no algorithm that can tell you if, from any state of the game, there exists a sequence of moves that yields a win. This holds when you assume an infinite map and infinite turns.

It’s not just that you could write (in theory) Minecraft with the Civ API and get it to run inside Civ:VI (think of writing everything in binary, directly talking to the hardware); but also that the number of possible states these games can take is infinitely large.

Civ’s undecidability is the most interesting thing. First of all, there’s lots of realistic Turing-complete games, but not many of them are undecidable. The only two I know of are Magic: The Gathering (formally shown in the reference), as well as Rengo Kriegspiel (a four-player, blindfolded version of Go; conjectured to be undecidable in “Games, Puzzles and Computation” by Hearn and Demaine).

Undecidable games imply that are alternative theories of computation based on games!

From a more practical perspective, it links formal algorithmic analysis to videogames (not for the first time). For example, the effectiveness of the class of algorithms you use to solve a difficult problem is usually determined by the hardness of that problem.

Since Civ is really hard, a good player cannot be written with simple algorithms (in Civ, the AI is a bunch of if-else statements lol). You need to use something more powerful, like a combination of deep-neural networks and reinforcement learning! We’ll talk about this more towards the end. First, some background.

Background

Computability

Computability means that there exists some sort of machine that is able to execute some set of instructions, and maybe return a result. For example, a light switch (‘when button pressed → let current flow to the lightbulb’), flipping a coin (‘when flipped, return randomly heads or tails’), or DNA replication (‘unzip molecule, read molecule, copy molecule...’).

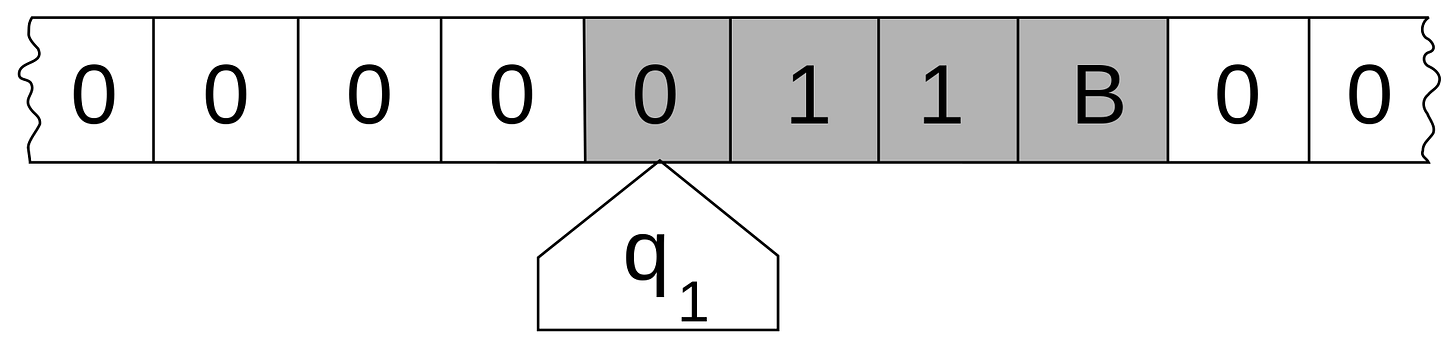

The mathematical model that we normally use to model computation is called a Turing Machine (TM). It is a mathematical object, equipped with an infinitely-long tape (hence the mathematical part), a way to keep an internal state, and a head that reads from the tape and executes instructions based on a function called the transition function.

A useful way to think about it is as a mathematical description of an algorithm, or computer program. For example, a TM adding two bits will have, say, an instruction saying ‘if I read 1 and my state is 1, write 0. Set the state to 1. Move the head to the right’.

This is why I said that you could write programs in Civ—the simplest way to do this would be in binary.

Note: The notion of a TM is so general, that a more accurate way to think about them is as a mathematical description of the act of computation. So not just computer programs, but also (e.g.) the process by which DNA replicates, or the way you are reading this sentence and determining its meaning.

It turns out that TMs, although they could run for an infinite amount of time and space, have a finite description (literally ‘this machine runs forever’). This can be represented as a finite string, and passed in to another TM for execution. Kind of how your browser (a program), runs on your machine’s operating system (also a program). A TM able to simulate any other TM is called a Universal Turing Machine (UTM).

Let me tie it back to the proof of Civ being Turing-complete. The proof consists of just one step:

Show that the rules of the game have an analogue with an existing UTM. When we allow for infinite space and time (just as in any other TM), we will have shown that Civ is able to simulate, in-game, a UTM.

That’s it!

Before that, it might be worthwhile addressing another point: suppose you can build such a UTM inside Civ (and we’ll see later, you can). That doesn’t mean the game is ‘hard’! It just means the rules of Civ allow for any program to be ran.

For the other bit, we need undecidability.

Turing-Completeness and Undecidability

It sounds like having infinite memory (or any unbounded resource) and the ability to simulate other computers means that a UTM is infinitely powerful.

Yes and no.

It turns out that the set of problems a computer can solve (call it R) is, in fact, rather small.2 A way to think about it is that there is no algorithm (TM) to decide whether an arbitrary, input TM will loop forever. This is known as the Halting Problem, and it is one of the central pillars of computation. Since there is no TM that can solve this problem, we say that the Halting Problem is undecidable.

Any mathematical or physical construct (a ‘model of computation’) that is as powerful as a UTM is, in fact, equivalent to it. That means that it can compute everything in R: no more, no less. Models equivalent to an UTM are said to be Turing-complete.

By this equivalence, it follows that a UTM could simulate any Turing-complete model of computation with some penalty to space or time. For example, your laptop is based off the Random Access model, and has limited memory. That means that a laptop, though amazing in its ability to run programs, is actually a lot weaker than a UTM. Then again, if you run out of memory, you could write a tiny program to prompt to you to add a new hard drive (i.e., you already ran out of RAM and are writing to disk instead). So it’s not really a problem.3

Examples of Universal Turing Machines

I’ll give three examples: the Game of Life cellular automaton, a class of neural networks, and Magic: The Gathering (MTG). The paper contains more examples (e.g., PowerPoint!), but I want to get right to the Civ stuff.

Each and every one of these models has two things in common: one, they can simulate an arbitrary algorithm (i.e., you can build a UTM inside of them), and, second, they are not realisable without an unbounded resource.

The Game of Life is a cellular automaton: an infinite grid where every cell takes in one of two states (”alive”/”dead”). It has some rules around evolution (e.g., if the current cell is alive but only one of its neighbours is alive, the current cell dies) which give rise to some very, very interesting patterns. It turns out that its rules are able to build a UTM--so, the ruleset is Turing-complete. More interestingly, it is not possible to determine whether from a state of the grid, another state will emerge, so the Game of Life is undecidable!

Did you see how you can’t go around building things?

Exactly.

Neural networks were shown in the 90s to be able to compute a function from a rather large class of functions (call it B). The model of computation is slightly different: you have a two-layer neural network, with some activation function, and it can approximate any element of B to an arbitrary precision. Since an alternative definition of R is “all numbers that can be approximated in finite time”, it’s simple to show that B and R are equivalent in a certain sense.

MTG is a card game. When I was a kid, I collected them because I liked the art. But turns out they are good for playing, too!

One can build a UTM in-game, and this UTM itself exists physically. The rules for a MTG UTM are the same as the game (and are written in the cards themselves). The tape is expanded dynamically by placing tokens (so, formally, the UTM does use an unbounded resource).

What is most remarkable about this construction, is that computation happens by forcing: it’s a two-player construct and the execution of any TM happens by simply following the rules. You could sit there all day “playing” without actually being able to do much.

This, in turn, also has some repercussions for regular MTG play: if you assume that there is no turn timer, and you have infinite tokens, you can run any TM. It then follows that MTG is also undecidable.

Did you see how you can’t go around building things?

Exactly.

Civ is Turing Complete

A Crash Course on Civ

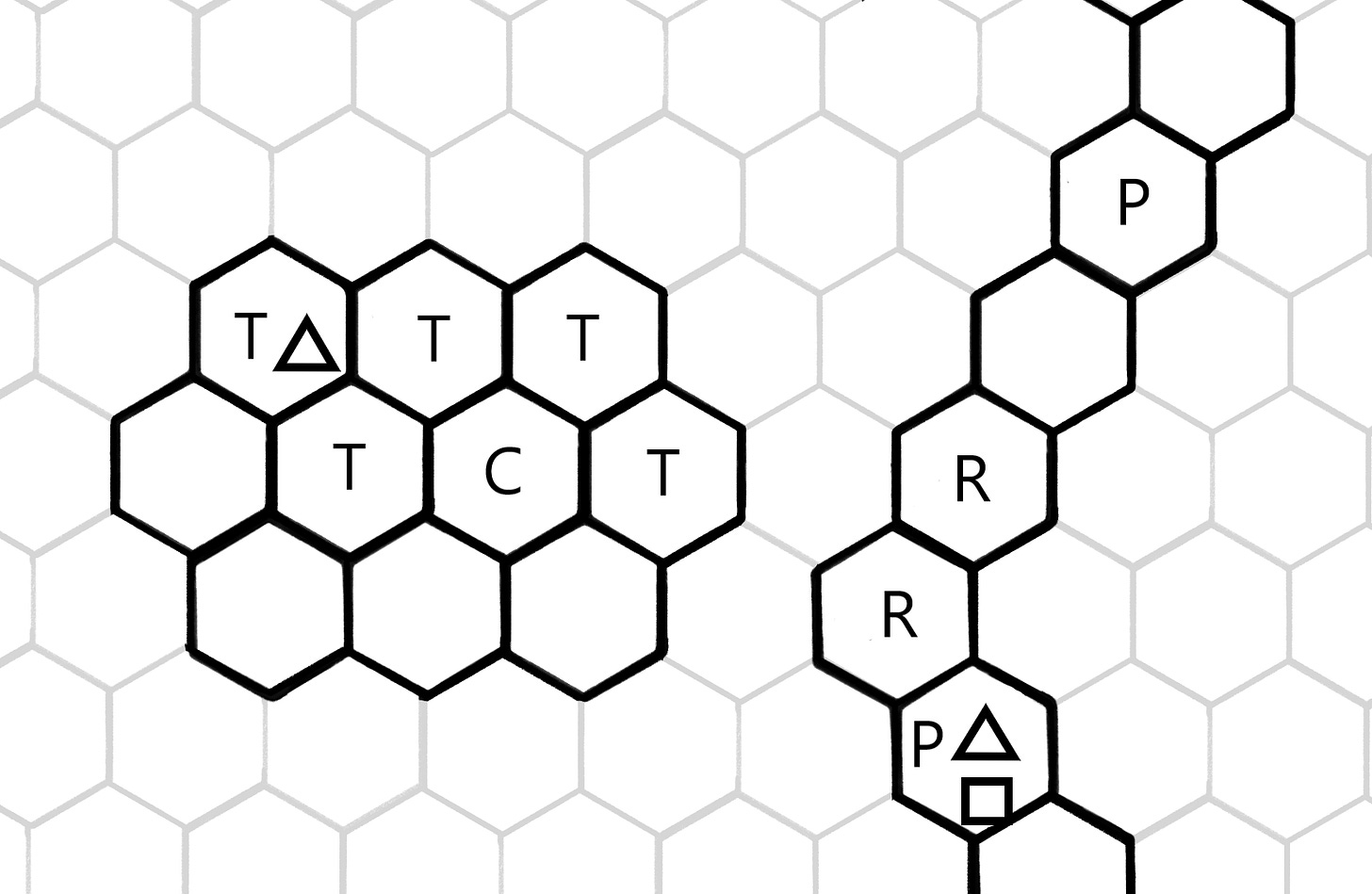

Civ is a complex, turn-based game, and explaining it in detail might warrant its own post. For our purposes, it suffices to note that you are in charge of an empire/extrasolar colony. It is played on a map divided in hexagonal tiles (”hexes”). You play against other players (usually the AI, in my case; I can’t handle human interaction), and you can win by meeting one of the multiple victory conditions. We won’t care much about them until our proof on decidability.

At every turn, you take most, if not all, of the actions available to you (e.g., moving a unit depends on the number of available moves), and focus on the overall management of your empire.

The backbone of your empire are the cities, which are in charge of producing units, expanding your borders, and producing resources via citizens. This last part is important: the citizens work the hexes and based on improvements you have built with a separate unit (the worker) the yields from these hexes change. For example, a citizen could work a base plains hex, netting you food (say) every turn, but if you were to build an Academy on it, it will yield science as well.

What we need to build UTMs is surprisingly little: a few rules plus some sort of unbounded resource (the map). We will also disable the turn timer (limit), which can be done from the setup screen (and thus it is not an assumption, since it is within the rules of the game).

Proof-wise, we also should assume that the other players don’t interfere with the computation, but if your map is infinite, that’s a relatively simple thing to achieve. In practice, I just set the difficulty super low and played against nice opponents. The first time I did this I had Alexander the Great, and that guy is really trigger happy ):

Civ is Turing Complete: Outline of the Proof(s)

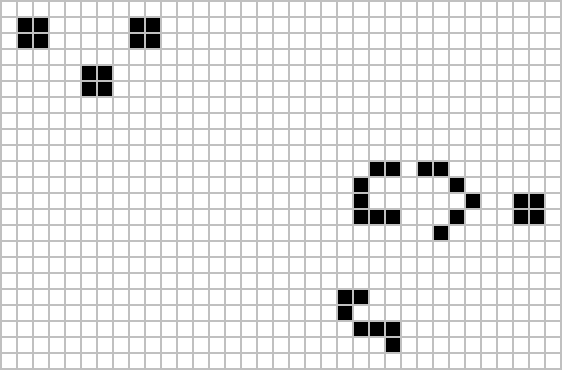

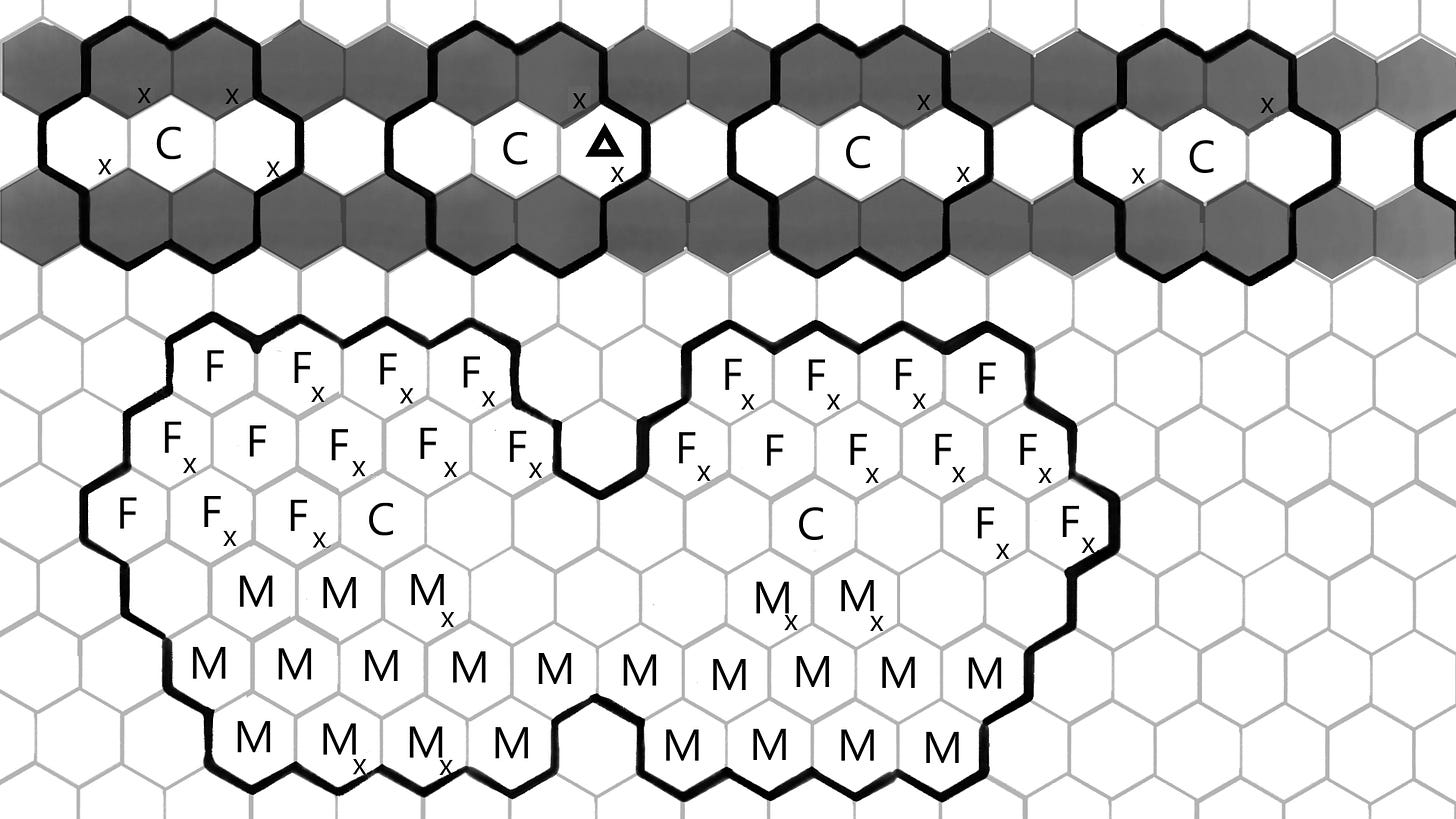

All UTMs can be seen running in-game as screenshots here.

We have three proofs: one for Civ:V, one for Civ:BE, and one for Civ:VI. The structure is very simple: We show that there exists a set of in-game rules and actions one can take that simulate the rules and actions of an existing UTM.

Then, in order to ensure that the simulation is not too slow, we also show that is bounded for any instruction.

This last part is not a strict requirement, but, if the game mechanics interfere in any way—for example, by having a specific TM that will take forever to simulate in-game—it would leave our construction infeasible.

Once we start talking about decidability, having a strict bound on the simulation time will be needed!!

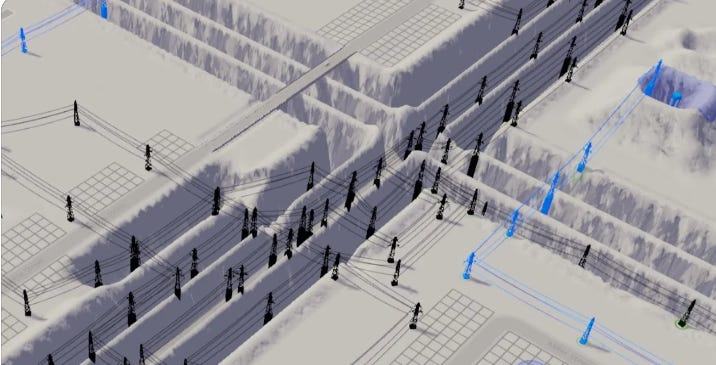

Civ:V and Civ:BE UTMs

In Civ:V and Civ:BE, you have access to a worker. This unit is able to build and remove improvements indefinitely. Crucially, some of these improvements can be built outside of your borders. So, the plan is as follows: we use one worker to build and remove improvements on the ‘tape’ (all of the map, minus a reserved section), and another worker to build and remove improvements as the ‘state’ (the reserved section; suppose it’s a city that you own). The tape worker is then the UTM head, and the state worker is, well, the way to update states.

In Civ:V, we will build roads and railroads. That means that instead of a binary symbol set (e.g., your laptop uses binary) we use a ternary symbol set on the tape. It makes no difference from a computational perspective.

We also use roads in the state worker. The worker moves left or right on the map and builds or removes roads/railroads accordingly. Interestingly, the delay is constant: the slowest instruction you will ever have executed in our Civ:V UTM is “remove one railroad and write a road”, which takes a fixed amount of turns.

In Civ:BE we can get a bit more creative, and make it also a ternary symbol set. Instead of building roads and railroads, we use roads (or magrails) and, along with the tape worker, we have a military unit (say, a rover). This unit executes parts of the instructions, and pillages an improvement.

So we have as our tape alphabet {road, pillaged, no improvement}. For the states, our state worker builds an improvement with a specific Culture yield (the Terrascape). We measure the state by checking the difference in total Culture yields every turn. Just as in Civ:V’s UTM, the overhead is constant, so this construction is 1:1 with a conventional UTM.

Civ:VI UTM

For Civ:VI we have to get really creative. This is because workers have limited charges and they can’t modify resources outside of your borders, which severely limits our options.4

So we won’t be using workers.

Instead, our tape is now going to be a chain of cities, and the symbols on the tape are going to be determined by whether a citizen is working a specific hex, or not. We can cap the growth of the cities to avoid complications; and we can use certain geographical features to ensure we actually have enough citizens (i.e., food).

Just as in the MTG UTM, our tape is not infinite from the start: we need to grow it as-needed, so we will incur a penalty in simulation overhead. To see where in the tape we are located, we’ll use a worker as the head. It won’t do much outside of telling us where we should be reading.

Analogous to the Civ:BE UTM, our state will be given by a resource accumulation. In this case we assume the player can build an improvement (a monastery), which is nicely behaved and yields a (sort of) constant amount of faith every turn. We assume the player has already built them, so we can swap citizens as needed in order to encode the state.

All in all, this is a very large and complex UTM. Due to the tape expansion scheme, this UTM runs linearly more slowly than a regular UTM. It’s also very brittle and hard to realise in-game.

But, it can be done! (which is the mathematician’s answer to everything lol)

We could always use cities and forests (chop and plant) to encode states. We could also build a two-player UTM where one player pillages roads and the other repairs them. So, while this construction is straightforward, it’s not the only or the simplest.

You probably noticed by now that these aren’t the only UTMs that are buildable within Civ! Can you find others?

(Un)Decidability of Civ

One thing you might have noticed is that all of our constructions used in-game rules and objects. In fact, there’s nothing stopping you from implementing this by using the API. Or by manually executing it, as we will discuss later.

This also has an important implication:

The states that are able to execute a computation arise naturally during gameplay.

Of course, in generalised gameplay (infinite map, infinite turns), the states that one can observe are much richer: in fact, they are precisely R.

So what does this mean?

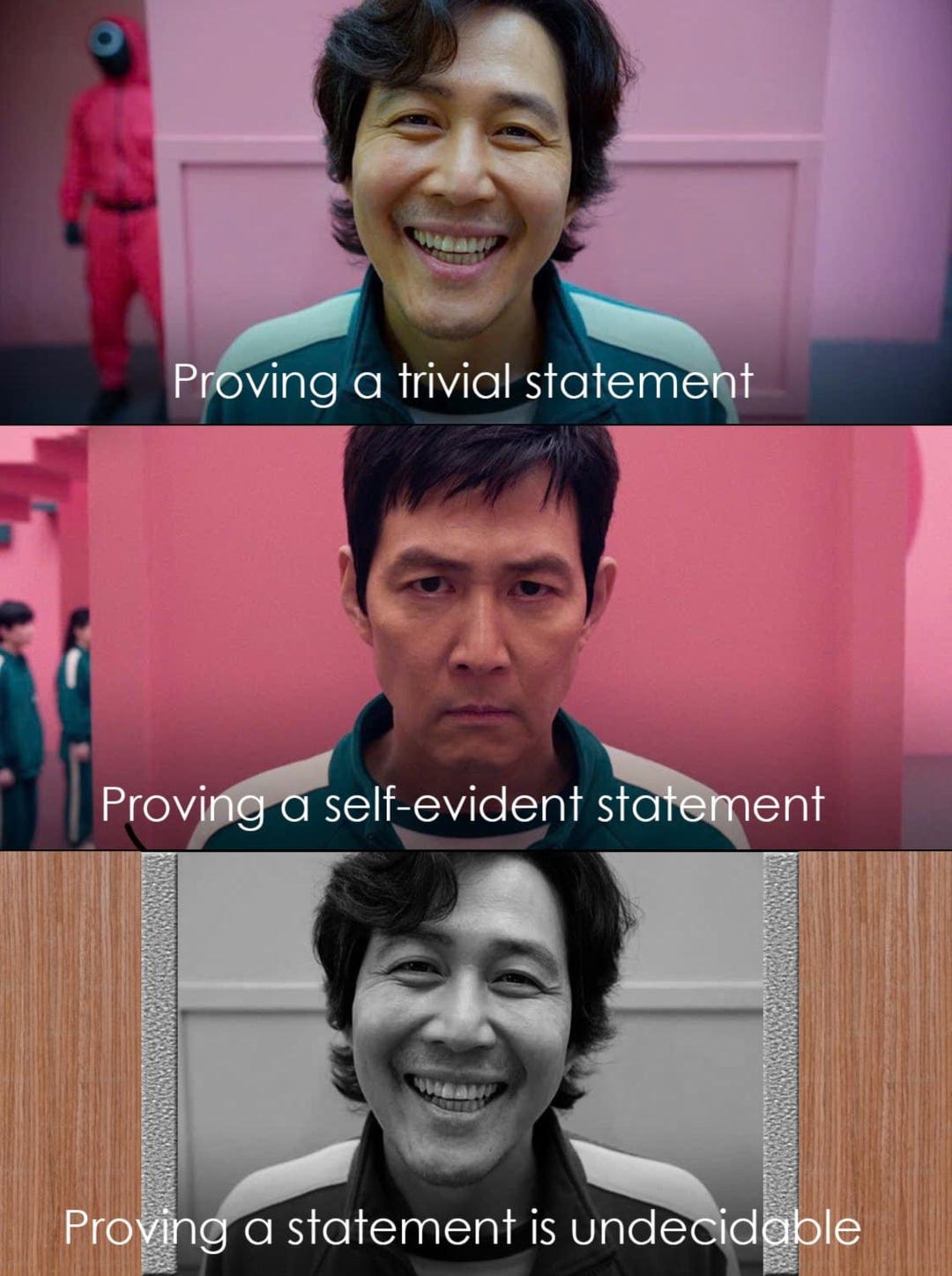

It means that (from the last section) you can build TMs to run inside the game. It also means that you can build a special TM (the UTM) that can simulate any TM. Which means, that one of the questions one can ask to this UTM is ‘does this (arbitrary) TM loop forever?’. As we saw earlier, this is the Halting Problem and it’s undecidable.

More interestingly, suppose you want to know if, from a game state, there exists a sequence of legal moves that yields a “forced win”: i.e., if you execute them, you win the game. So:

This is a step-by-step process, so it is an algorithm.

This is therefore a TM.

This TM can therefore be simulated in-game with your UTM.

Then the question ‘Does produce a forced win with these steps?’ is equivalent to the question ‘Does halt given this TM?’

We know this question: it’s the Halting Problem!

So the problem of determining a winning sequence of moves in (generalised) Civilization V, VI, or Beyond Earth, is undecidable!

Or, in English:

You can’t answer that question! There’s no algorithm for that!

Or, cooler:

(Generalised) Civilization V, VI, and Beyond Earth are amongst the hardest games in existence!

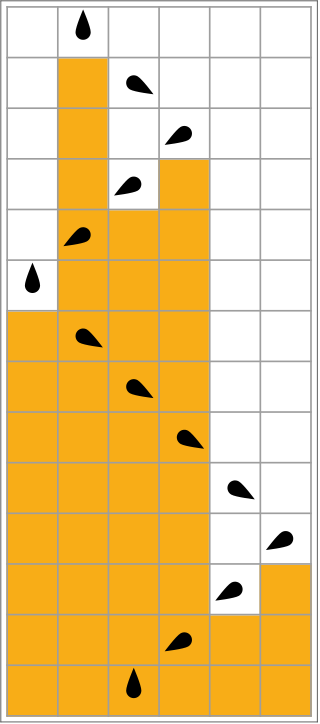

An Application: Building BB-3 in Civ

I want to close this section with a short example of how closely related a TM is to an actual Civ state. For this, we’ll be talking about a TM that ‘wins’ the Busy Beaver game.

The implementation and execution is here.

These are a bunch of screenshots of me simulating the thing manually. This would be equivalent of you doing a multiplication with pen and paper.

Theoretically, these states can be read by hardware, and then turned into a calculator/computer/etc. But good luck doing that lol.

Anyway.

The Busy Beaver challenges the player (human/TM) to find the smallest n-state TM that outputs the most number of 1s on the tape. The winner is called the Busy Beaver, or BB-n.

Note how many ‘theoretical’ problems actually appear frequently in realistic applications. BB-3 could be thought of as a similar, Civ-like, question: suppose there’s some scenario where you win the game if you built the most roads in the map. Naturally, you would win if you wrote the most roads the fastest.

So, you want a small TM that solves that problem. In particular, you would want to find a Busy Beaver. If you are constrained in resources (e.g., you can’t afford to maintain all of these workers!) you would need to calibrate the ‘n’ in BB-n.

While this is still somewhat unpractical, note that there’s nothing stopping us from observing something similar in the game—and actually executing it, as we saw.

It also does not need unbounded resources.

More importantly, the problem of finding BB-n for arbitrary n is undecidable. So, there are questions you can ask to the game that have no answer. In fact, although now I’m repeating myself, the problem of determining a forced win is undecidable.

Even this imaginary scenario, since it is BB-n! This should not be surprising by now: the game is running on a computer, so everything that a computer/UTM can’t do won’t be able to be done by Civ. However, it is indeed surprising that it cannot be answered by the rules of the game either—no matter how powerful they are!

This is a common pathology of UTMs. For example, most programming languages are Turing complete. But deciding whether an arbitrary program will error out or compile and run correctly is the same as the Halting Problem.

In fact, one could say that a Turing-complete ruleset is able to ask and answer the same questions any other Turing-complete ruleset can. One of these rulesets turns out to be mathematical proofs!

So What?

Implications for Actual Civ Gameplay

There are two things I’d like to talk about. One is how realistic our assumptions were. The second is whether there are any applications for this, or other work. I just spent like two hours writing about problems one can’t ever solve, so it is time to talk about practical stuff.

Turing Completeness irl

What about the non-generalised versions of Civ—i.e., Civ with finite memory and finite time?

It turns out that the results for Turing-completeness and undecidability change, but not that much.

In the case of a computer versus a TM, a computer can solve the infinite tape requirement by prompting the user to add more tape (e.g., a new hard drive). For example, back in the 90’s you needed to install games by inserting CDs in sequence; so the computation/tape expansion argument is rather general. This argument, originally given by Hopcroft et al., can be adapted to our UTMs without much hassle.

For example, a very naïve implementation would just duplicate the state hexes (which are constant size) and use multiple computers and saves to simulate extended tapes. This does not require a modification of Civ’s code,5 but any TM being simulated would have to include that wee overhead. Then again, we already have samples of that intrinsically written as part of Civ:VI’s UTM (or, e.g., MTG’s).

We can also measure how often we will end up needing to expand the tape.

Alternatively, the question is: how much memory does a Civ UTM have?

We can do this by estimating the number of internal states for a UTM. In the case of Civ:V, on a single ‘Huge’ map size (as a loose upper bound) we have 128 x 80 hexes, minus 10 for the state-tracking.

Then the UTM for Civ:V has

possible configurations (where |Q|=10, |Γ|=3 are the sizes of the state set and tape alphabet, respectively).

It’s kind of small, since a computer with 128 Mb main memory and a 30 Gb HDD has this many states:

It’s still quite a bit of memory for a wee game! :)

Complexity of Civ irl

Let’s consider the problem of writing AI to play the game effectively. We’ll start with an ‘easier’ problem: chess. You can take an arbitrary state of the (say) n x n board, with the pieces in some arrangement, and then be tasked to determine whether you can win.

This is the same question as in Civ’s proof of undecidability. To solve this problem, you must ‘play’ some moves and rewind time. That is, if you move a piece (call it x), you have 2n possible moves. In your next turn, you will have available 2n moves (likely outcomes), but these are conditioned on your previous moves, which is conditioned in the movement of x… etc.

We can see that:

It’s a HUGE number of possible movements, and

It behaves like a tree (since it’s a branching decision process!)

The number of possible movements (a.k.a. the ‘branching factor’ of our tree) in chess is quite large. Too large to use conventional, tree-based search algorithms, like A*!

So what is the branching factor in non-generalised Civ?

That’s still an open question. But, for generalised chess, it’s exponential. So, to properly solve generalised chess, you will need exponential time on n, something like

where k, p are constants.

We call that class of problems EXPTIME. Generalised chess, some forms of Go, and other games are in EXPTIME. The difference between EXPTIME and, say, generalised Zelda games (which is in PSPACE, the class that is solvable by using tape cells) is a bit fuzzy for reasons we won't go into detail here, but your choice of algorithms to play the game are still dependent on its complexity.

What does this have to do with AI for Civ?

The effectiveness of the algorithms used to ‘play’, ‘solve’, or ‘approximately solve’ a problem (a.k.a. a heuristic), is strongly dependent on how hard the problem is.

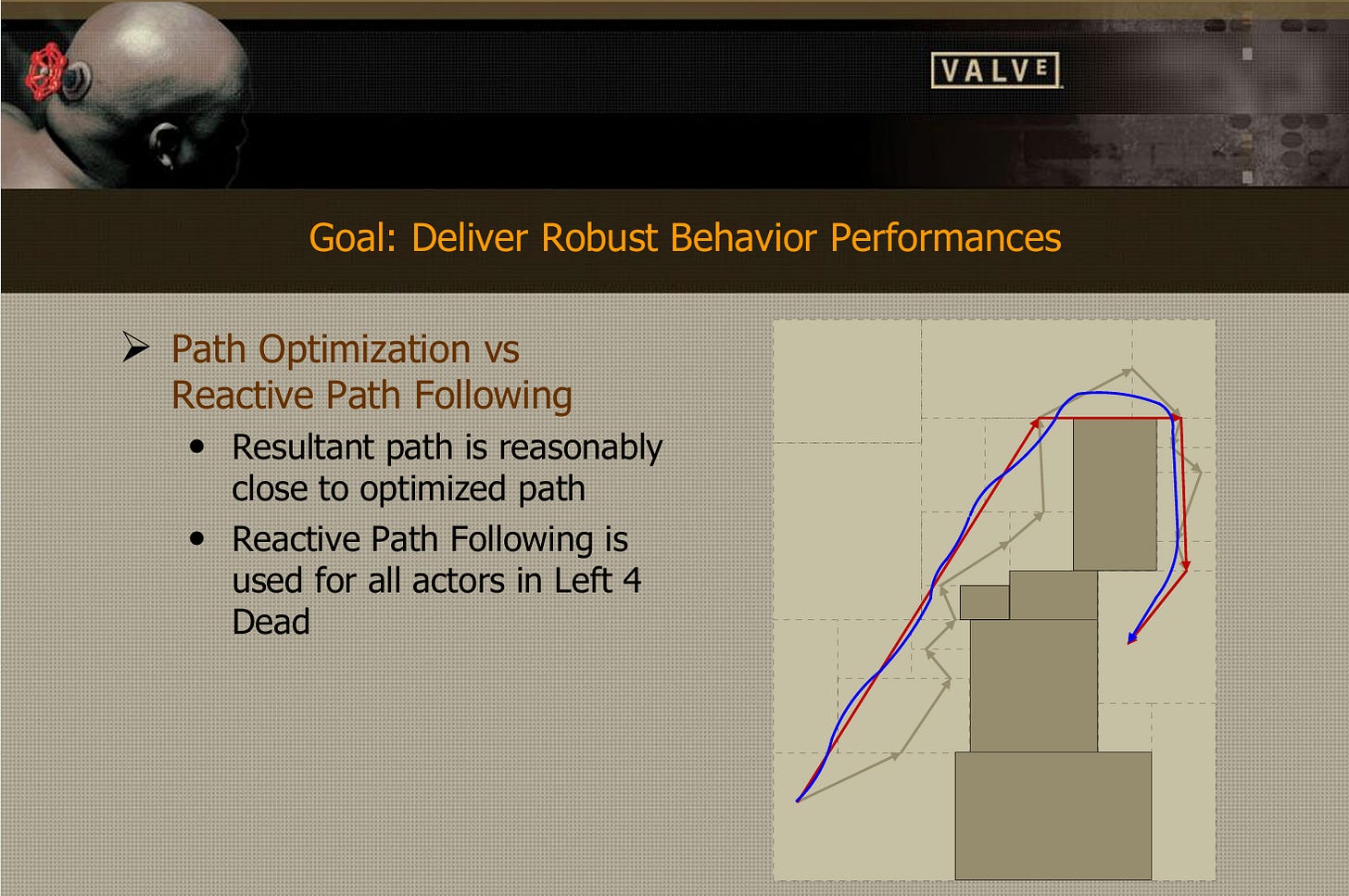

AI play games by solving problems, such as path-finding in FPS. Here’s an example of the then-groundbreaking AI used in Left 4 Dead 2. It is safe to assume that an FPS is an ‘easier’ game,6 and path-finding heuristics would work well (as seen there).

Trying to solve a problem with such a large branching factor (the problem here being ‘how to win at Civ every time’) suggests that using more powerful algorithms would be needed.

For example, AlphaGo Zero smashed records in Go by using a combination of non-linear models (neural networks) as well as a heuristic for pruning the tree, known as the Monte Carlo tree search. Nobody actually told the model how to win the game, but it inferred the rules and eventually developed a very unique play style.

The AI in Civ currently uses a mixture of if-else statements, as well as ‘cheats’ (bonuses) in higher difficulty levels. This makes the AI quite predictable, and thus easy to play against if you know what you’re doing.

If Civ happened to be ‘easy’ (e.g., in PSPACE), maybe an array of modified path-finding algorithms could work. But if it’s harder than Go, we probably will be stuck in if-else land for a while.

Where computational complexity theory really shines is in showing that some problems are equivalent to one another. turns out bounded Go is PSPACE-complete, so in a sense, an algorithm that solves bounded Go also solves Zelda games. This means that one could ‘solve’ one problem by first transforming it (reducing it) into another, and then just solving that instead.

But first we would have to show that Civ belongs to any of these classes!

Implications for Theoretical Computer Science

I mentioned bounded Go as being PSPACE-complete and EXPTIME-complete otherwise. Hearn and Demaine showed that two-player games with perfect information are in general EXPTIME-complete. So, generalised chess, generalised Go, and all these games where you can actually see your opponent’s pieces are decidable (and relatively nice, since the ‘complete’ means that they are reducible among problems within the same class). They also show that imperfect information games are in general undecidable; even when they are space-bounded in some cases.

But what does this mean with respect to Civ’s undecidability and Turing-completeness?

If we lift the unbounded space assumption, but allow for unlimited turns, the game (now with a full-on opponent) is still very likely undecidable. But how can this be? This means that a very real game (I always play without a turn limit anyway) is able to manipulate bounded resources to perform arbitrary computation (that is, compute the infinite set R).

Hearn and Demaine point out that this is more of a physics question. One could subscribe to the ‘many-worlds’ interpretation of quantum physics, apply that to a quantum computer, and assume that the ‘you’ that was able to execute arbitrary computation in polynomial time is the ‘real you’.

Games-as-computers suggest an alternative: you execute arbitrary computation, and the players execute the moves. The space requirement is not part of the computation, but by having infinite memory (by the players) or maybe by forced wins (like in MTG) you can still do it in bounded space.

While this might sound kind of weird, think of quantum entanglement: there, you transmit information seemingly faster than the speed of light. But, since information cannot travel faster than the speed of light, the entangled measurement will yield a uniformly random outcome until you have observed the other measurement (which cannot happen faster than the speed of light).

Conclusion

We learnt that generalised Civ can execute any algorithm, and that it is impossible to determine whether a sequence of moves yields a win within this game. However, our argument relies on having an infinite-sized map, and no turn limits.

In practice, these constraints may seem unrealistic, but even without one of these constraints—and, in fact, under regular, strategic play—the games are undecidable, and hence amongst the hardest games in existence.

This is not an exaggeration. All models of computation are equivalent, so it doesn’t quite matter if you run Civ on a laptop, super computer, or DNA strands: R is still R.

The findings have interesting repercussions for Civ and for research in the computational complexity of games. Namely,

Building effective AI for Civ and other similar games requires powerful, state-of-the-art algorithms. Not if-else statements.

I also conjecture that for an arbitrary map size (but still finite) and unbounded turn times, the games should be in EXPTIME-complete. That means that they must be at least as hard as (generalised) chess! This is a very realistic problem: when you set up your game, you have an arbitrary map size (with mods, even more so); and you can disable the turn timer.

An effective reduction from Civ to a known problem in, say, EXPTIME-complete, will very likely also provide information about other 4X games. In spite of their very different mechanics (even between installments, most Civs are quite different) all 4X games have the same ‘multiple resources, multiple games, multiple victory conditions; but bounded space and multiple-actions per-turn’ theme going on. So it is quite probable that they are also reducible amongst each other.7

All in all, I hope you liked this post. Like Fry would say, it took a few hours to write, so I thought it’d take a few hours to read. But hopefully you found it interesting. I particularly think that the addition of computational complexity theory to actual videogame play could yield some very interesting results. Plus, I love this field.

If not, you can think of it the other way:

It’s quite possible that the study of games will yield even more interesting results in theoretical computer science!

In the words of David Hilbert: ‘wir müssen wissen. Wir werden wissen’.

Technically, R is called the set of decidable languages (return “yes” if the answer is “yes” and “no” if the answer is “no”). By definition, the Halting Problem is not in R. TMs can answer a slightly larger set--as long as the answer is “yes”. Otherwise, they may loop forever. This set is called RE (for Recursively Enumerable), and the Halting problem is in that set. But that’s beyond our discussion, since we want an algorithm that always terminates.

Aside: complexity theorists kind of gloss over the Halting Problem and study the recursive hierarchy created by (imaginary) machines that could solve the Halting Problem. Turns out these machines can’t solve a “super” Halting Problem, and so on. We really won’t be discussing that, but I think it’s pretty cool. :)

It drove nuts because Civ:BE is my favourite, but Civ:VI is the one I spent the most time on AND COME ON I HAD TO DO SOMETHING PRODUCTIVE WITH ALL THAT TIME DAMN IT

For example, in Civ:VI you could use the starting seed and some constant initial time to configure the state hexes; in Civ:V/BE you could use mods to pre-populate the maps

It is in PSPACE, if you want to get technical.

A minor nuance in this conjecture might be diplomatic victories for Civ:VI: a player can decrease or increase their “diplomatic score”, and once this score reaches a certain quantity, you win. We know that if we lift the turn limit you can actually have an infinite loop where you increase-decrease your score, so they might be undecidable then.